Introduction

The Domesday book, compiled in 1086 on the orders of William the Conqueror, remains one of the most extraordinary documents in European history. Created only twenty years after the Norman conquest, it was designed as a vast and meticulous survey of landholding, resources, population, and taxable value across much of England. Reminiscent of the Roman census, something to estimate the class of citizens for both military and tax purposes, nothing quite like it would exist again for centuries. For historians, it offers a glimpse of the English landscape in the late 11th century. The transition of Saxon England to the new Norman one.

Within this record lies the entry for North Petherton. A significant royal area in Somerset, situated between Bridgwater and Taunton. Its listing in the Domesday Book offers not just a snapshot of who controlled the estate at the time of the Norman survey, but also a detailed catalogue of the land, its inhabitants, agricultural capacity, and monetary worth.

Like many Domesday entries, the language is technical and difficult to understand. And understanding the document firstly requires a close look at the text and translating it into an understandable format. By doing so, we can appreciate the landscape that it describes.

The Text

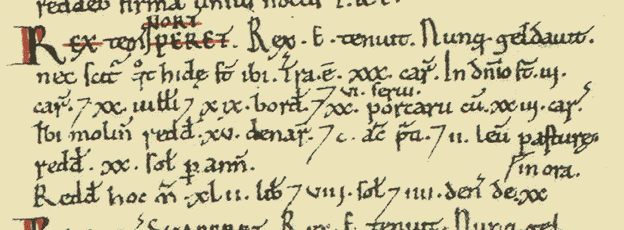

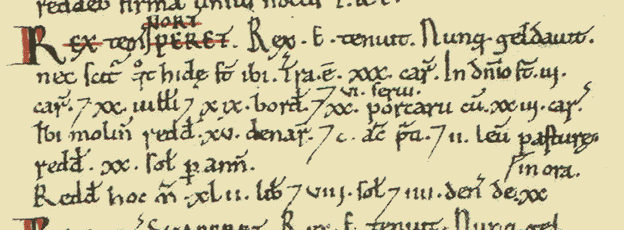

Original Latin:

NORT

REX TRE PERET. Rex. E. Tenuit. Nunc geldauit.

Nec scit qe hide fi ibi. Tra.e. xxx. Car. Indnio fi. iii

Car. 7 xx. Uilli 7 xix. Bord. 7 xx. porcaru cu. xxiii. Car.

Ibi molin redd. xv. Denar. 7 c. de pa. 7 ii. Leu pastura.

Redd. xx. Sol. P an.

Redd hoc n xlii. Lib 7 viii. Sol 7 iiii. Den de. xx

____________________________________________________

Simplified Latin:

Nort Peret. Rex Edwardus tenuit tempore regis Edwardi. Nun geldavit.

Nec scit quae hida fuit ibi. Terrae XXX carrucatae. In dominio fuit III carrucae et XX villani et XIX bordarii et XX porci cum XXIII carrucis.

Ibi molinum reddit XV denarius et C de pastura et II levatae pasturae. Reddit XX solidos per annum.

Reddit hoc nunc XLII libras et VIII solidos et IV denarius de XX.

____________________________________________________

Word-for-Word Translation:

North Petherton. King Edward held it in the time of King Edward. Now it pays geld.

It is not known how many hides of land there were. There are 30 Ploughlands in total. In the Lordship, there were 3 Ploughlands, and there were 20 Villeins and 19 Bordars and 20 pigs with 23 ploughlands.

There, the mill pays 15 pence, plus 100 pence from pasture and 2 levies of pasture.

The land pays 20 shillings per year.

The total value now is 42 pounds, 8 shillings, and 4 pence.

____________________________________________________

Simplified Translation:

In the time of King Edward the Confessor, North Petherton was held by the King. At the time of the Domesday survey, it was recorded as paying tax. The exact number of hides of land is unknown, but the manor contained 30 ploughlands in total.

Of these, 3 ploughlands were held directly by the lord, while the remainder were cultivated by tenants. 20 ploughlands were worked by villeins and 19 by bordars (smallholders). The manor also supported 20 pigs associated with 23 ploughlands.

There was a mill on the estate, which brought in 15 pence in addition to 100 pence from pasture and two pasture levies. The manor generated an annual rent of 20 shillings.

The total value of North Petherton at the time of the Domesday Survey was 42 pounds, 8 shillings, and 4 pence.

____________________________________________________

A Note on the Original Passage and the Translation

Translating medieval Latin is no easy feat. My knowledge is in Classical Latin, which, although similar, may contain some differences. Primary Latin is typically difficult to understand even with a good understanding of Latin since it commonly contains abbreviations (see above words like Car, Denar, Sol, and TRE). As you will be able to see, I have expanded these abbreviations for clarity in the simplified Latin. Additionally, you may notice the use of “7”. This is visible in the original entry; however, it refers to the Tironian 7, which is a shorthand way of writing “et”.

In short. The original Latin is a direct, readable transcript taken directly from the Domesday Book with original abbreviations and symbols, while the Simplified Latin has expanded on these symbols and abbreviations to make the Latin readable in full. I then, in Word-for-Word Translation, directly translated the Latin to English, which is a challenge in itself. It is rather coarse and blunt. However, following this, I further translated this into Readable English in theSimplified Translation, which, using context, was able to produce a more readable and understandable English translation while staying true to the content of the original passage.

The translation is my own. Due to the versatility of Latin, others may translate this passage differently; however, this translation is the basis of this article.

Ownership

One of the first things that the Domesday book tells us about North Petherton is who held it, who was in charge of the manor and received its income. The entry says “Rex Edwardus tenuit tempore regis Edwardi (In the time of King Edward (the Confessor), The King held it)”. It might sound a bit odd at first, but it simply shows us that the manor in North Petherton and the surrounding lands belonged directly to the King himself, not to a church, local lord, or noble family. Therefore, North Petherton was not just any settlement; it was royal land.

This in itself tells us three important things. Firstly, it was valuable, secondly, it was well established, and thirdly, it was strategically important.

After the Norman invasion, William the Conqueror replaced King Edward, keeping North Petherton, meaning that at the time of the Domesday survey, the manor was still Royal property. The continuity of this is interesting since many estates changed hands dramatically after the conquest, taken and redistributed to Norman followers and supporters of the King; however, North Petherton remained within the King’s estates, as later history also attests.

Why does the Domesday Book mention this first? Well, it is a recurring trend in the Domesday book that each entry begins with the ownership of the land, since in Medieval England, land basically meant wealth, and wealth meant power, so by leading the record with “the king owns this land” is simply saying “this place matters”.

For the people of North Petherton in 1086, Royal Ownership likely meant that there was more organisation and supervision, higher expectations for productivity, greater protection, and a more stable administration. This means that North Petherton wasn’t just a wild or remote settlement in 1086, but an established village connected to national power.

Therefore, within the first line of the Domesday entry, we can tell that North Petherton was already well established, mattered enough for the King to keep it in his royal lands, and was likely fairly wealthy.

How big was the estate?

After telling us who owned North Petherton, the Domesday entry turns to explain the size of the estate. This part of the text can look confusing since it uses old land measurement terms that don’t really match anything we use today. But once they are explained, the picture will become clearer.

The Domesday book states, “Nec scit quae hida fuit ibi. Terrae XXX carrucatae (The exact number of hides of land is unknown, but the manor contained 30 ploughlands in total).”

A hide is not a fixed measurement like an acre, but instead, a taxable unit. A way of saying how much land was supposed to contribute to the king’s revenue. So, where the Domesday book tells us, “it is not known how many hides there were”, it is simply telling us that by 1086, the old tax rating was unclear or unknown.

Most importantly, we are met with the term “Ploughland” or “Carucate” in Latin. This is the amount of land that could be worked by one plough team of eight oxen in a year. Essentially, a full-sized working farm that could grow enough crops to feed many people, unlike smallholdings, which usually produced enough for a family. So, where the entry records thirty ploughlands, it is telling us that North Petherton had enough arable land to support thirty full farming units, which is a vast amount.

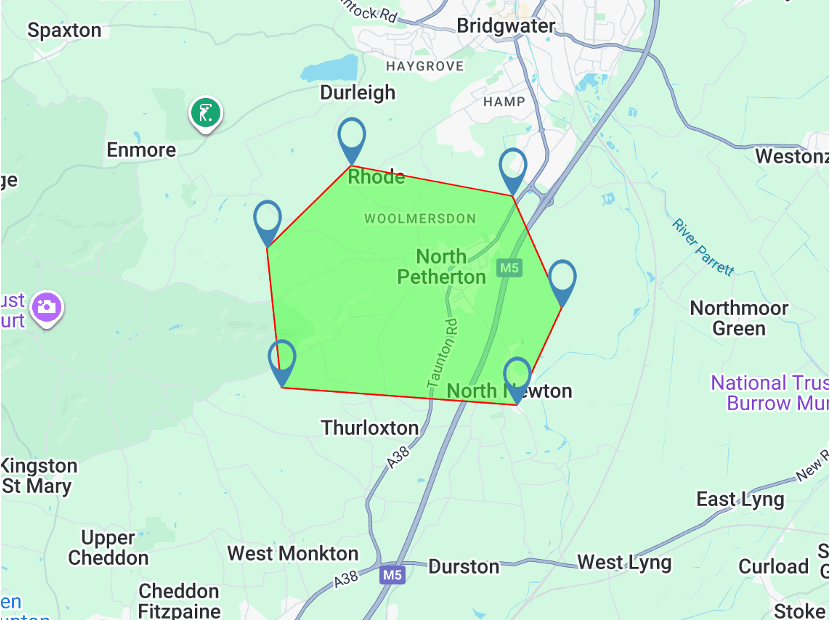

While the exact acreage varied, it is generally estimated that in modern terms one ploughland was roughly 120 acres, meaning that in total there was around 3,600 acres of arable farmland around North Petherton, which you can see compared in the image below. (Note this is not the land area, just a comparison)

This shows us that North Petherton was a major agricultural estate producing a significant amount of food and wealth.

We also find how the land was divided. “In dominio fuit III carrucae (In the lordship there were three ploughlands)”. This explains that three of these ploughlands were farmed directly for the king, while the remaining 27 were worked by the people. Therefore, the crown was taking a hands-on interest in part of the farmland, not just collecting the rent.

Overall, from just two lines, we can see that North Petherton was a large and highly productive agricultural area, part of which was kept by the king for direct use.

Who Lived in North Petherton?

Once the Domesday book has laid out the size of the estate, it moves on to describe the people who were living there, and I don’t mean “Mr and Mrs Saxon of 1 North Petherton had brown hair and blue eyes and were 5’6” and liked a good sing song”!

The entry records the community and their roles that helped North Petherton to function in 1086. “XX villani et XIX bordarii (20 Villeins and 19 Bordars)”. Now you might be wondering what a Villein and a Bordar are. Villiens (not villains!) were the main working farmers, while Bordars were smallholders (smaller farming households).

Villeins had their own homes and farmed their own land (around 30 acres) but were still very much indebted to the manor. They were not slaves; however, they could not easily get up and leave the manor lands since they owed work to their lord. They formed the backbone of rural society. Importantly, the Domesday Book records working households. Not individuals. Therefore, it is not saying there are twenty people who owned land, but rather twenty households – around 100 people in total, depending on family size. This again is significant. It is a large settlement with a substantial farming population.

Bordars, on the other hand, were smaller farming households, similar to later burgage plots. They had small plots (around 5 acres) of land where they kept garden crops or animals (sometimes both), and they often worked part-time on the lord’s land and other land in the area, especially at times of harvest. Again, this number refers to households rather than individuals – around 90-100 people at a guess.

Additionally, some of you may go on to read what is available on the Open Domesday website and notice that it records there being 6 slaves (servi). The entry does not explicitly mention any slaves; therefore, this data is likely based on other records or perhaps uses other records in the vicinity to guess at how many slaves may have been present.

Though this is useful information, the Domesday book does not usually count wives, widows, children, elderly relatives, servants, craftsmen/townspeople, priests, or dependants. So we can take a guess at the population based on this, which may total around 200; however, if we take into account other members of the community, we could be seeing numbers closer to 300. Again, showing us a large agricultural community.

Farms, Animals, and Resources

Alongside the people and the ploughland, the Domesday Book offers a glimpse of the other things that made North Petherton productive in 1086. The animals, the grazing land, and the mill. These details are easy to look over at first, but for medieval life, they were important aspects of daily living.

The Domesday entry tells us – “XX porci cum XXIII carrucis (twenty pigs associated with 23 Ploughlands)” and “Ibi molinum reddit XV denarius et C de pastura et II levatae pasturae. (There, the mill pays 15 pence, plus 100 pence from pasture and 2 levies of pasture)”.

Pigs were a medieval staple. They fed themselves in woodland, provided meat for salting over winter, were cheap to keep, and were very common among households. While 20 pigs aren’t a huge amount compared to other manors, it does show us that there was a mixture of farming taking place and what the population would have been eating.

Mills were even more important in the 11th century. Bread was eaten every day. As a classical historian, agrarian societies are at the heart of civilisation. In fact, civilisation only ever grows around three main staples. Grain, Rice, or Corn. Carbohydrates that can be grown en masse, stored dry, and made into goods like bread. Simply, it is a cheap and easy way to feed people and keep their stomachs full. North Petherton, having a mill, tells us that there was enough grain to support a mill (i.e. bread was being produced in large amounts, unlike smaller communities where flour would be ground by hand). Additionally, we can see that flour or bread is likely a good that is being exported, since the king is receiving income from it (15 pence may not seem like much, but it proves regular use and a steady revenue). Most manors did not have mills, so again, this places North Petherton on the wealthier and more important side.

The entry also records that there is an income of 100 pence from pasture. Pasture mattered because animals needed space to graze, and animals were essential for multiple reasons. Oxen pulled ploughs, Sheep provided wool, milk, and meat, cows produced manure (fertiliser), milk, and meat, and goats produced hides, milk, and meat. Income from land used for pasture shows us that the land was supporting livestock, and it was valuable enough to charge for grazing. As a Historical economist, it also shows us that there was likely industry involved, probably in the wool trade, which would have been the reason it was able to be taxed.

The obscure reference to “two pasture levies” is a bit confusing; however, it likely refers to additional payments, arrangements or seasonal grazing charges. Either way, it shows us that pasture was an organised and profitable part of the manor.

Unlike some Domesday records, we don’t actually see a list of full livestock numbers beyond the pigs, namely because most recorded livestock belonged to the lord. It doesn’t mean that the animals weren’t there, rather that the surveyors didn’t record them. From the evidence of households and ploughlands, we can expect around 200 oxen, again a substantial number. However, other animals appear to elude us.

It would be safe to assume that there were sheep, as these are one of the most common livestock animals in England, based on other entries. Chickens were also common household animals (producers of eggs, feathers and meat). Cows are perhaps the most complicated ones to place, and we simply do not have the data to guess, although there may have been some, but not in the herds we see today, perhaps two or three living on smallholdings.

But from the entry, we can see that North Petherton produced a large amount of grain, kept pigs and grazing animals (likely sheep) and was able to support a substantial number of oxen. It was not a marginal settlement, but a busy and productive one that was able to generate income.

Manor’s Value and Worth

After looking at who lived in North Petherton and what resources the manor had, the Domesday book also tells us how much it was worth. This is where the survey gives us a sense of the estate’s economic worth and importance, not just the land, but also how much it could produce.

The entry records “Reddit XX solidos per annum. Reddit hoc nunc XLII libras et VIII solidos et IV denarius de XX (The land pays 20 shillings per year. It pays now 42 pounds and 8 shillings and 4 pence)”.

To begin with, let’s look at what these numbers mean. In 11th-century England, 1 pound was made of 20 shillings, and 1 shilling was made of 12 pence. To put it simply, this is a substantial amount. Most manors were valued at a few pounds, meaning that North Petherton was likely one of the wealthiest estates in the area.

The 20 shillings initially discussed (paid per year, annum) is most likely the rent or income from certain parts (farmland or tenants), while the total value reflects everything from the pasture to the mill.

For North Petherton, we do not find a pre-conquest figure as seen in some other examples, but what we can tell is that post-conquest, the estate was of some economic significance.

Some Latin speakers/readers may have noticed the final two words “De XX (of 20)”, and be wondering what it means; however, it is primarily a way of showing how geld (tax) was calculated. It does not change the value, but instead refers to the way that the tax was assessed, e.g. the total value of North Petherton was 42 pounds, 8 shillings, and 4 pence, with a tax assessment connected to 20 units (geld).

Why North Petherton Matters

It is clear that North Petherton was more than just a name on a page in 1086. It was a thriving, productive and important community. Before the Norman Conquest, it was held by the crown, and afterwards it remained so, meaning it was well managed, economically valuable and closely connected to the crown. We even see that the King kept a portion of the land to farm himself (well, through tenants), which shows how important it was.

We see the extent of the productive agricultural landscape. 30 ploughlands made it a large and fertile estate, and resources like pasture, pigs and a mill show us that it not just produced food to feed itself, but a surplus that allowed for extra income.

We also see the people who were living in North Petherton. Up to 300 people, consisting of Villeins and Bordars, who were the engine of the estate, working the land, tending to animals and producing goods like food or perhaps wool.

And finally, we see the economic significance. The valuation of the manor and the income generated that meant that tax was so high. It was one of the most prosperous places in the area, with wealth that did not just support the community, but the king too.

We can see North Petherton in a way that other sources cant, we can build a picture and imagine the families that worked the fields, the oxen dragging ploughs, the sheep grazing, the creak of a mill producing flour and the grunt of pigs. We can understand why it mattered.

Leave a comment