The Cathedral

Peaty water ripples around a peaceful little island cemetery, but this river once bubbled with blood, boiling from the clan feud that scars Skye’s landscape. For most, it is a tranquil place to rest; for Skye’s teenagers, it is a place for summer gatherings, to leap from the high banks into the deep(ish) river below. For others, it can be a leisurely afternoon stroll, down the short path and over a narrow wooden bridge. But this is no ordinary island.

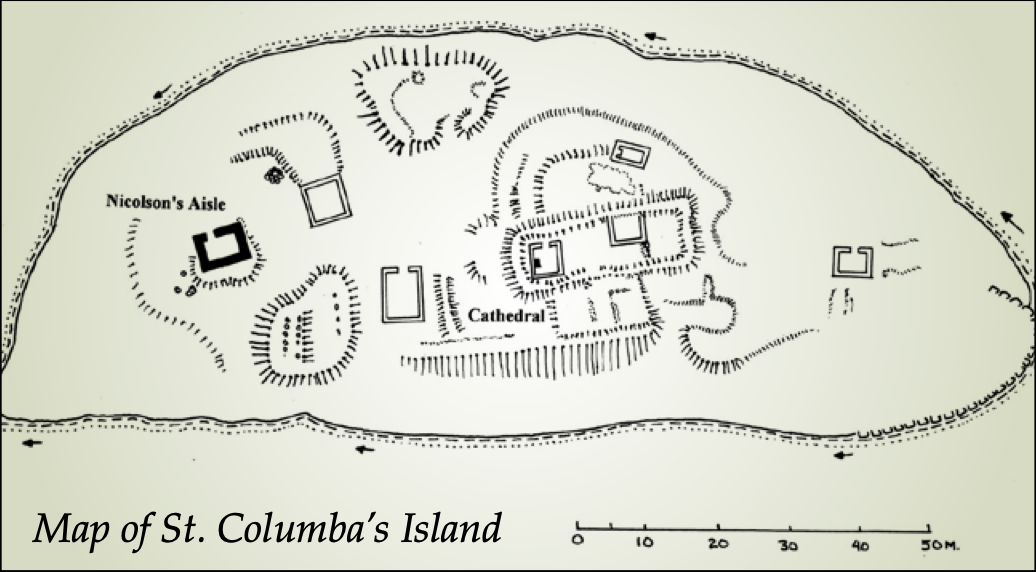

As you enter St Columba’s Isle on the River Snizort, there is a small central ruin, barely visible now due to the overgrowth and placement of newer graves, but do not let its size and elusiveness fool you. This was once a cathedral. Yes, granted, it is no St Paul’s or Vatican City, but it was once a cathedral, nonetheless.

Snizort Cathedral was founded sometime in the 11th century CE. Its location is close to St Columba’s Rock, where he had preached Christianity some five hundred years earlier (now lost but probably close to the site of the Skeabost memorial hall). At the time of the cathedral’s establishment, Skye was under Norse rule; therefore, Snizort Cathedral was established under the authority of the Archbishop of Trondheim in Norway. Until the defeat of the Norse by Alexander III, King of Scots, in 1265, when control then passed to the Lordship of the Isles. It survived to the end of the 15thcentury, being the seat for the Bishops of the Isles (the base of Catholic churches in the Hebrides and the Isle of Man). Including being the seat of its first and most interesting Bishop, Wimund, who was also known for being a seafaring warlord adventurer during his time as Bishop of the Isles (But that’s a story for another article!).

Just before the 15th century turned into the 16th, in 1498, the cathedral became obscure, with the bishops of the Isles moving to Iona, leaving Snizort cathedral to fall into ruin, with the Scottish reformation further destroying it. At its height, it is clear from the surviving ruins, historical records, and LIDAR that there was certainly once a monastic settlement here. Historic surveys suggest that before the cathedral was built, the island had a stone enclosure with 5-6 chapels within, although only two survive today.

The remains of the cathedral are 22.5 metres in length, 6 metres in width, and would have likely stood around 2 metres tall. The shape is typical and cruciform, with two later added transepts (the smaller two buildings that make a church or cathedral into a crucifix shape). There is a circular remnant at the western end of the cathedral, which would suggest a tower, perhaps in a similar style to St Magnus Kirk on Orkney; however, Scottish churches rarely have towers. It is highly likely that there was uniformity or similarities to St Clement’s Church at Rodel on Harris; therefore, if you are wondering what it may have looked like, there is a rough image below!

The Graveyard

Cathedrals were not just places of worship, but also places of burial. If you peer between the gaps in the ancient stones and crumbling graves, then St Columba’s Isle has far more history to discover. For one, it was a sacred burial place, and not just for the bishops who worked there. For 900 years, it was where the chieftains of the Clan Nicholson, one of the prominent clans on Skye, were buried, twenty-eight of them historically, but also more recently it is where the ashes were scattered of Chief Iain Nicholson in 2004. Martin Martin, in his 1703 Description of the Western Highlands, describes St Columba’s Isle as “(A) burying-place for all the chiefs of the tribes about the island.”, which is not fully the case since it seems only the Nicolson chieftains were buried here. One of the chapels, the easternmost one, known as Nicolson’s Aisle, is thought to be the burial location for these chieftains. Early scholarly accounts refer to this chapel as the Church of St Columba, with it possibly being the original Norse church. Excavations in 1992 discovered some rather fascinating finds relating to the burial proceedings of Clan chiefs. They discovered the ground surface to be covered with broken glass from wine bottles, suggesting that it was one of the ways that clan members could say their farewells.

Not all graves belong to chiefs though, the graveyard also features several examples of high-status warrior graves. These are often misreported as either “Gallowglass (mercenary warriors)” or “crusader graves”, although this is almost certainly a romanticism; therefore, it should not be taken at face value. These warrior graves are some of the best surviving effigies in the Hebrides. These are carved in a typical west highland style, which was used for over two centuries from the 14th to the 16th, featuring warriors in quilted coats, bascinets (open-faced helmets), and banded mail, with hilted swords. They are very similar to the carved tomb of Alexander MacLeod of Harris, found in St Clement’s Church, Rodel, on Harris, which at first glance (and as some have speculated) would suggest the same craftsman. However, with dating issues, it is hard to prove since three of the Skeabost tombs could date as early as the 14th century. Although the fourth, known as the Nicolson Effigy, found inside Nicolson’s Aisle, depicts its figure with a claymore, certainly dating it to the 16th century, which is a similar date to the Rodel tomb.

Additionally, another effigy, known as the MacSween Effigy, provides equal discourse. Unlike the other examples, this particular tomb contains three lines of three letters in the top right corner, “MMS, RMS, and IHS”. In almost every source I have read, it is assumed that these are initials. Although this does not explain the small figure in the right-hand corner, which I believe is the image of a saint. I would instead argue that these may be Latin inscriptions. As a Classicist by trade, I am no beginner when it comes to confusing Latin epigraphs, not helped by the consistent abbreviations and acronyms to fit words or cut costs of engravings. This would certainly need further investigation; however, it is my belief, and I would strongly argue that these three inscriptions could be Latin, standing for –

MMS – “Mater Misericordiae Sancta (Holy Mother of Mercy)”

RMS – “Rex Mundi Salvator (King of the World, Saviour)”

IMS – “Iesus Misericors Salvator (Jesus, Merciful Saviour)”

As a catholic cathedral, Latin would have been widely used administratively; therefore, it is not impossible for this new reading to be inaccurate. Even the final line could be read as “IHS (Iesus Hominum Salvator (Jesus Saviour of Men))”, which was a common inscription on medieval tombs. And before you start wondering why an M was used instead of an H, it is incredibly common for mistakes to be made in Latin inscriptions! Especially in a time of low literacy and high oral tradition. Alternatively, IMS could well be a localised variant of the standard IHS Christogram, adapted by Gaelic or Norse-Gaelic speakers in a form of “Folk latinising”. Interestingly, this provides us with an example of how Island Christianity was not purely a passive receiver of continental religion, but was also creative and adaptive, possibly showing how local craftsmen attempt to recreate what they have seen elsewhere. These different readings also adapt how we read the slab. Does this grave belong to a member of the MacSween clan or their family, or is this a religious invocation?

You may also notice a tomb with a skull and crossbones on it… and no, it’s not what you think. Unlike other posts and articles that jump to “pirates” or “the plague”, I am only here to deal in facts! And unfortunately, it is not nearly as fanciful as these other writers make out. Skulls and crossbones or general images of death are common throughout Scotland from the 17th to the 18th centuries. They are purely decorative as symbols of morality, and they even have a name – “Memento Mori”. If you explore the graves around Scotland, you’ll find countless examples ranging from skulls and crossbones to scythes and hourglasses, and even crossed spades to symbolise the gravedigger.

Whatever the truth of these inscriptions, there is no doubt that these graves speak of a world of violence, class and faith. They are not just decorations like the memento mori, but also the self-images of clans who lived and died by the sword. And nowhere speaks of this more than St Columba’s Isle.

The Battle

In 1539, a clash erupted between the MacLeods of Dunvegan and the MacDonalds of Sleat, two rival clans of Skye. The feud has festered for years, with constant brutal massacres and battles dotting the medieval landscape, eventually culminating in the final and bloodiest clan war that Scotland had seen, needing royal intervention to end it (see two of my previous articles on this – War of the One-eyed Woman and Massacred at Mass). This particular battle, the Battle of Trouternes, has hazy (and often misreported or assumed) origins. Like many pieces on Scottish and Hebridean history, it is not helped by the lack of sources. However, many that I have read in my research differ on which clan held the lands of the Trotternish peninsula, the northern spine, which gives the battle its name. But this is, from my research of the primary materials and understanding of both clans’ histories on the island, my conclusion of how the battle came to be.

It started when the MacLeods, led by their chieftain Alasdair Crotach MacLeod, attempted to reseize land across the loch and river Snizort. They held lands west of the River Snizort down to Elgol (see the Clan map of Skye for a rough estimate of the lands), and had held the Trotternish peninsula until 1528, when they were driven out by a combined MacDonald of Sleat and MacLeod of Lewis army, which caused issues on a national level, with the Privy Council requesting both chieftains to appear before the king, but they did not.

The MacDonalds were led by either Donald Gorm MacDonald (died 1539) or his brother Archibald (The Cleric). Though I would argue it was likely Donald Gorm, since he was on a bit of an expansion rampage before his death at Eilean Donnan Castle, while Archibald was simply standing in as the Chief until Donald Gorm’s son, Donald Gormeson (You can see why people get confused!), was a child waiting to learn the ways of leading a clan.

Nonetheless, the two forces met on the banks of the river Snizort, the exact location of which is unknown, though there is a marker of the battle near the Skeabost Country House Hotel. Geographically, Skeabost would indeed be a likely candidate, especially since there were stepping stones across the river at St Columba’s Isle, allowing people to cross the river easily.

What came next was nothing short of slaughter. The battle is also known as the Battle of Achadh na Fala (the field of blood), though “field” is perhaps the wrong term. Warriors hacked at each other as the MacLeods attempted to cross the river. Heavy mail and armour dragging men beneath the river’s current. Some will have drowned, while others met the cold steel of Scottish swords. Clan histories state that the river literally “ran red with the blood of the fallen”. It is likely that the MacDonalds set up a defensive position on the eastern bank of the river, sending some to attack the MacLeods in the water, ruthlessly spearing any of their enemy who attempted to crawl onto the bank to escape the bloodshed.

But the battle did not simply end in a MacLeod Defeat. The MacDonald chief (probably Gorm) is said to have beheaded his fallen enemies, throwing their heads into the river in a true brutal Hebridean clan rivalry insult. However, they did not simply wash out to sea. They were caught in the current as they bobbed along, becoming trapped in a sort of whirlpool near St Columba’s Isle until they settled as skulls, their skin rotted and washed away.

This pool is still visible today. I previously mentioned the stone commemorating the battle, which is located near the Skeabost Country House Hotel, and if you walk along the riverside between this hotel and St Columba’s Isle, then you will find a little castellated power station near the commemoration, which is where the pool is. It is known as the “Coirre-nan-Ceann”, roughly translated to be the “Cauldron of Heads” or “Skulls”; however, the skulls have likely disappeared over the last 500 years.

Considering the river’s current, the commemoration is probably not a marker of the battle site, though you may find many blogs and secondary sources using it as a basis. Instead, the battle likely took place further upstream, which would allow the heads to be washed down to their final watery prison. There was, however, a cairn commemorating the battle on the western bank of the Snizort (roughly where the Skeabost Country House Hotel now stands), but this was destroyed in the 19th century.

The MacDonalds were victorious, and the Battle for Trotternish (Trouternes) had won them the peninsula, or at least for the time being, had managed to expand their influence into the peninsula. However, as with all Scottish history, it was only a part of the whole story!

The Aftermath

Although the battle had been won, the clan war was far from over. I mentioned at the beginning of this article that this was one of many events leading up to the culminating war of the One-Eyed Woman (again, you can read more about this here), which required royal intervention to stop the bloodshed. However, unlike many other sources that I have read over the years, and in preparation for this article, this battle was not directly part of the war. Many would have you believe that it was, although if you simply look at the dates, the Battle of Trouternes (1539) and the start of the War of the One-Eyed Woman (c. 1601), then it does not take an expert to point out that the events were 60 years apart! However, they were a part of a bitter, ruthless and bloodthirsty feud and rivalry that had existed for centuries since the two clans emerged from the feudal and war-lord systems that were stitched into the very fabric of the Hebrides and Scotland.

Skye’s clan borders were constantly shifting. Though crown records show tenant holders and tell us who held land, the reality in the Hebrides was that lands were in a constant, fluctuating state, made harder to read due to biased clan histories and accounts. Therefore, it is difficult to precisely know what happened, but from a detailed analysis and examination of the sources and contextual evidence of wider clan battles, this article, I believe, is close to the truth of the events that took place on the banks of the River Snizort in 1539.

Sources:

Clan MacNicol Federation (n.d.) Saint Columba’s Island, Clan MacNicol Federation. Available at: https://clanmacnicol.org/St-Columbas-Island

Clan MacNicol Federation (2024) The Southern Cross, The Journal of Clan MacNeacail in Australia and New Zealand. vol. 32, no. 3, December, pp. 1–12. Available at: https://clanmacnicol.org/sites/default/files/2024-12/Vol%2032%20No%203%202024.pdf

Gaelic Rings (2016) Gaelic Ring: Skye – Historical Overview, in Gaelic Rings/Cearcaill na Gàidhlig (ed.), Gaelic Rings, Wayback Machine, archived 3 March. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20160303173703/http://www.gaelic-rings.com/skye/index.php?top=1&mid=1&base=7&ring=Barra

MacDonald, A. and MacDonald, A. (1900). The Clan Donald. Vol. 1. Inverness: The Northern Counties Publishing Company, Ltd.

MacDonald, A. and MacDonald, A. (1900). The Clan Donald. Vol. 2. Inverness: The Northern Counties Publishing Company, Ltd.

MacDonald, A. and MacDonald, A. (1900). The Clan Donald. Vol. 3. Inverness: The Northern Counties Publishing Company, Ltd.

Mackenzie, A. (1881) History of the MacDonalds and Lords of the Isles; with genealogies of the principal families of the name, Inverness: A & W MacKenzie.

MacKenzie, A. (1885) ‘The History of the Macleods’, Celtic Magazine, vol. XI, no. CXXI, November, Inverness: A. & W. Mackenzie.

MacKenzie, A. (1894) History of the Mackenzies. Inverness: A. & W. Mackenzie.

MacLeod, F.T. (1910) “Skeabost Burial-ground,” Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol. 44.

MacLeod, R. C. (1927) The MacLeods of Dunvegan. Edinburgh.

MacRae, Rev. Alexander (1910) History of the Clan Macrae. Dingwall: George Souter.

Nickelson, J. (2015) A Brief History and Archaeology of St. Columba’s Isle at Skeabost, Clan MacNicol Federation, Scorrybreac.

Nicolson, A. and Maclean, A. (1994) A History of Skye: a record of the families, the social conditions and the literature of the island, Maclean Press.

Roberts, J. L. (1999) Feuds, Forays and Rebellions: History of the Highland Clans, 1475–1625. (illustrated ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Smith, A. (c. 1865) The Island of Graves 1865, in St. Columba’s Isle, Snizort.net (no date), accessible at: https://snizort.net

Images from:

Am Baile (n.d.) Graveslab detail, St Columba’s Island, Skeabost, Skye, HighLife Highland / Am Baile. Available at: https://www.ambaile.org.uk/asset/39487/

Gvdwiele (2011) Saint Clement’s Church in Rodel, Isle of Harris, Western Isles, Scotland. Wikimedia Commons. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15979416

Jones, B. (2009) St Magnus Kirk and Graveyard. Wikimedia Commons. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14034860

Nickelson, J. (2015) A Brief History and Archaeology of St. Columba’s Isle at Skeabost, Clan MacNicol Federation, Scorrybreac.

Sunbright57 (2018) ‘St Columba’s Chapel at Skeabost, Isle of Skye, Highland Region, Inner Hebrides’, The Journal of Antiquities, 24 October. Available at: https://thejournalofantiquities.com/2018/10/24/st-columbas-chapel-at-skeabost-isle-of-skye-highland-region-inner-hebrides/

Leave a comment