Odin and Odda

In 878 CE, twenty-three ships harboured between the sandy banks of the Parrett Estuary. Grey smoke rose from a scattered camp close to what is now a grain store, as an army estimated at one thousand two hundred laid siege to a seemingly insignificant and unprepared hillfort. The power of Odin emanated from war chants and rhythmic drums, and the clash of Thor’s forge boomed as they smithed and sharpened their axes in preparation for war. The black raven banner fluttered victoriously in the salty sea breeze that combed Combwich, woven by the daughters of the legendary Viking king Ragnar Lodbrok, supposedly with magic that could foretell the outcome of a battle, flapping strongly to signify victory or lulling limply for defeat.

Odda looked out from the rickety walls that he had reinforced, smoke billowing from the campfires below as the murmur of the besiegers growled, as if the camp itself were hungry for blood. He was the Ealdorman of Devon, loyal to King Alfred, who for the moment was hiding in the marshes of the Somerset levels just under ten miles away at Athelney. He could see the ships in the distance, the estuary, Steart beach, and several prominent hills from Brent Knoll to Dowsbrough. It was a defensive position well suited for observing an approaching army. However, his overall position was far too weak. The army at his back was nothing more than armed farmers and peasants, their supplies were likely few, and there was no source of fresh water within the fort’s walls. As he watched the raven banner fly in favour of his enemy, Odda’s odds were far from ideal.

Ubba headed the besieging Viking army, one of three sons of Ragnar Lodbrok, who led the so-called Great Heathen Army on a ruthless, revenge-driven conquest of England following their father’s death at the hands of the Northumbrian King Ælla. They had landed around thirteen years earlier in East Anglia, but their exact strength remains debated. Estimates range from less than a thousand (David Sturdy, 1996) to over five thousand warriors (Richard Abels, 1998). While the exact number of warriors remains elusive, the scale and duration of their campaign suggest a substantial force.

Asser’s Life of Alfred records 350 Viking ships attacking Canterbury almost 15 years earlier, in 851 CE, seemingly as part of routine raids on England. In a catalogue of Viking ship sizes by Peter Sawyer (1962), we can find an estimate of how many men a ship could hold. A small longship could carry perhaps 30-32 men, whilst a great longship could hold between 65-70 warriors, and the largest Knorrs (cargo ships) could transport up to 250 men. Therefore, applying this logistical evidence to the recorded attack at Canterbury, we could estimate the raiding party’s size to plausibly be between 10,500 to 87,000 men. This would far exceed what 9th-century logistics could support; however, we find ourselves faced with a decent example of exaggeration often found in medieval chronicles. Even so, we must also consider that even if there were 100 ships, they would have likely only been half full of warriors to allow them to transport supplies, animals, loot, and slaves.

A more grounded comparison is found in the Siege of Paris in 845 CE, where a recorded 120 ships laid siege to the Frankish city. An estimate of around 5,000 men is commonly accepted to be an accurate size of the besieging army, which would correlate with Sawyer’s data, however, it is important to note that medieval battles were not as they are presented in popular TV shows like Game of Thrones or films such as The Lord of the Rings. In fact, they were far from it. Battles were often fought between a few dozen to a few hundred soldiers, nothing like the larger-scale organised warfare of Ancient Greece and Rome or later medieval kingdoms. These were not career militarists; instead, they were mainly peasants and farmers who took up arms in times of need, with a few exceptions. When the Great Heathen Army landed on English shores, they were not fighting a single army; they were fighting lots of smaller battles and smaller forces, therefore, ten thousand plus, though it would indeed obliterate any resistance, would also certainly be overkill.

We must also consider the fluidity of the Great Heathen Army. As a force that eventually came to settle, there would have been many others who came alongside the warband. Craftsmen, enslaved people, free traders, and women, for example. Though many may have fought within the main military force, a presence was needed to maintain stability in the areas they conquered. Additionally, as they progressed, they would have likely been joined by their new subjects as they forged new alliances with the local elite, as well as others from Scandinavia and northern Europe, while perhaps some returned home after some time, leading to an army that would have been in a continual flux.

After they landed in 865 CE, they tore through the English kingdoms. First, they took York and killed the Northumbrian King Ælla, supposedly executing him with the brutal “blood eagle” in revenge for the death of Ragnar. They installed a puppet King in Northumbria and turned toward Mercia, and then East Anglia. Once victorious, they began their assault on Wessex. With reinforcements from Scandinavia landing in the summer of 871 CE, they clashed furiously with the West Saxons, led by King Æthelred’s brother, Alfred (later crowned King and given the title “the Great”). Alfred had been victorious at the Battle of Ashdown, but when crowned King, he attempted to pay off the Vikings for peace. It worked, for a time, as unrest in the north took their attention away for a while; however, by around 876 CE, the Vikings had begun raiding Wessex again and in January of 878 CE, a Viking attack on Chippenham (where Alfred had been staying), depleted a large part of his forces and forced him into hiding in the Somerset marshes.

This is where we began. As Alfred hid, the Viking army is thought to have split into two in an attempted pincer movement. Guthrum, one leader, attacked Somerset from the North-East (Gloucester), whilst Ubba sailed around the coast and launched his attack from Dyfed (Wales), and attacked from the North-West. As the Vikings laid siege to the fort, likely smug with the sense of an impending victory, what happened next was what they least expected.

Odda, knowing that his position within the unprepared fort was weak, knew that he would not be able to outlast the Vikings below. So, he did the only thing he could. One dawn, he and his men burst from the gates of the fort, taking their attackers by surprise. After what would have been a brutal and messy battle, Odda proved victorious, defeating the Vikings and slaying a recorded 840 of the supposed 1,200-strong army, including Ubba. This battle would go on to be known as the Battle of Cynwit and was the first in a chain that eventually led to Alfred’s great victory. And it was fought on the marshy fields between Cannington and Combwich. At least, this is what I argue.

The Battlefield

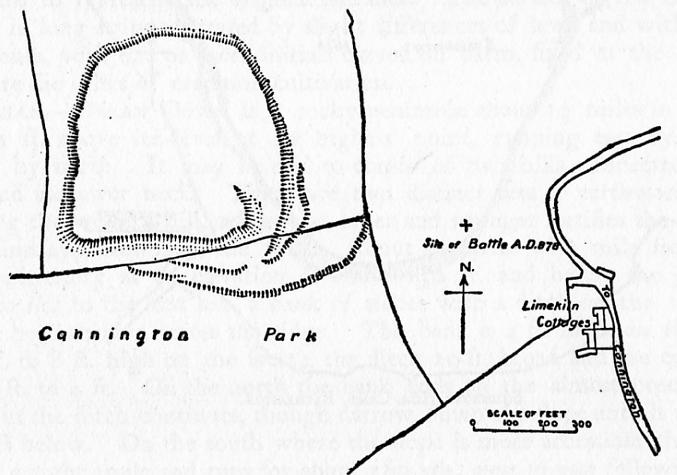

The exact location of the Battle of Cynwit is disputed. However, the most argued locations are either Wind Hill (Countisbury) or Cannington Camp, and the majority of these sources seem fairly certain that the battle was fought at Countisbury; however, I suspect that this is not the case.

We can be fairly certain that the location was along the north coast of the southwest Peninsula since the Viking army was recorded to have wintered in Dyfed (Wales) not long before the battle; therefore, this would discount any suggested locations on the southern coast. Though Countisbury is the generally accepted location, I would be far more confident in putting Cannington Camp forward as the most likely location for the battle.

Firstly, the geography of Countisbury would not suggest a vulnerable location for the Vikings to attack. I would argue that the extremely steep cliffs and inaccessibility of landing areas (other than the beach at Lynmouth) would more likely lead to the Vikings further traversing the coast for a safe arrival. Cannington Camp, on the other hand, seems far more geographically suited for a Viking landing. Flatter land with the addition of the River Parrett, a traversable river that would allow them to sail inland. From first-hand accounts of the Viking raids on Europe, we can find that this is far more comparable to their usual modus operandi, rather than skinny beach landings and cliff-top assaults. Additionally, if we are to take into consideration the wider events of the time and the possibility that Ubba’s motive for the attack was to indeed catch Alfred in a pincer movement, then surely Ubba would have wanted to land closer to where Alfred was hiding, rather than adding a further thirty miles (as the crow flies) to their assault.

Secondly, I would argue that the location of “Devon”, which is stated in contemporary sources, is one of the reasons that Countisbury has been preferred over its Somerset counterpart. Combined with Odda being the Ealdorman of Devon, I must admit that taking the primary sources at face value would suggest that the battle could not have taken place anywhere else. So why would Asser and other chroniclers record the battleground as Devon rather than Somerset?

Anglo-Saxon England didn’t really have the counties that we have today. Granted, some existed, but they were different. The Dumonii were an ancient tribe, recorded by the Romans during their occupation of Britain. Their kingdom, Dumonia (where the name Devon comes from), encompassed Cornwall, Devon, and large parts of Somerset and Dorset. However, during the 6th and 7th centuries, a westward Wessex expansion began to erode its reach. By the early 9thcentury, it barely exceeded the bounds of modern Cornwall. Therefore, it is entirely possible that by this time, the territory between the River Parrett and the Cornish border could have been referred to as “Devon”, including what is now known as Somerset, since the people living there would have likely still identified themselves as Dumonii (or Devonians).

There may also have been confusion or an unawareness surrounding Odda’s role within the battle. Perhaps his association as the Ealdorman of Devon led chroniclers to believe that it was where the battle took place, when instead he potentially recruited his army as he tracked the Vikings along the north Devon and Somerset Coast until their engagement at Cannington.

Additionally, etymologically, it makes more sense. Combwich (pronounced Kummij), a town equally close to Cannington Fort as Cannington, would more closely match the traditional pronunciation of Cynwit. For the Anglo-Saxons and Old English, the pronunciation would be closer to German; therefore, “cyn” would be closer to Kun (with an “oo” sound), and “wit” may be related to, or be a mistake, of the Old English Wich (or Wic), which refers to a coastal settlement that is characterised by extensive artisanal trade. Suggesting that the pronunciation of the fortification would likely be “kuunwich”, which may have evolved into Combwich. The Domesday book records the area as “Comiz”, coming from the Old English “Cumb” to mean a settlement in a short, open valley. If we take into account discrepancies in spelling and phonetic spelling, then it is possible that “Kun” may have been mistaken for “Cumb” and “Wit” for “Wich”.

Therefore, if we are to take these considerations into account, Cannington Camp makes a likely contender as the site of the battle. The geographic landscape, especially, points to an area more suited to a Viking landing. Alongside the possible misconceptions and tactical decisions, I would say that it is the most likely contender for the location.

The Battle

Sources record that the Vikings landed with 23 ships and that the Saxons slew eight hundred and forty Norsemen, which would suggest at least thirty-six men per ship. Using Sawyer’s data (as mentioned earlier), we could possibly agree with Asser’s estimate that the army would have been around one thousand two hundred, especially if we are to believe that they utilised great longships to traverse the Cornish peninsula and had at least fifty men per ship. Although there may be some discrepancies in the recorded numbers, it is a useful and probably fairly accurate statistic to have since it can help build a better picture of the size of Viking armies. I would argue that perhaps the full army that landed was not present at the battle; small bands may have gone off to regroup with Guthrum’s larger army, some likely stayed closer to the ships, and some may have sailed further inland. Therefore, it is possible that the entire besieging force may have been slaughtered.

The number of defending Devonians (or Somersetian Saxons) is unknown. However, it was certainly large enough to defeat the Vikings. This may perhaps suggest a smaller Viking force, since Cannington Camp or Wind Hill could likely not hold more than 800 grown men. However, if we are to take the evidence at face value, perhaps it is possible that with such a surprising attack, the Saxons could have been successful with as few as 500 men, although I would argue that the numbers could have realistically been anywhere between 600-800.

We know from Æthelweard that it was Odda who led the Saxons; however, the exact leader of the Vikings is never explicitly mentioned in contemporary sources. The only mention we have is that the leader was a “brother of Hingwar (Ivar) and Halfdene (Halfdan)”; therefore, it is clear why the leader is often referred to as Ubba. I’m tempted to agree with this conclusion since the records (at least four sources) are fairly consistent with this identification, and with Ubba commonly accepted to have been at the head of the Great Heathen Army, alongside Ivar and Halfdan, we could safely assume this leader to be Ubba.

Sources are also consistent in their description of the battle, although it is very basic. In all accounts, Odda took Ubba’s forces by surprise, perhaps the only way to overwhelm a larger force. Though they state that it was dawn when the attack occurred, perhaps an attack shortly before dawn, under the cover of darkness, would make more sense. The hit series The Last Kingdom presents an interesting idea of sabotage beforehand as the protagonist sneaks into the camp to burn the ships. Though what is shown after, the single combat between Ubba and Uhtred, is less likely, it could potentially be possible that some men snuck out of the fort to create a distraction, dividing the forces and allowing for a Saxon victory, though it cannot necessarily be confirmed. Additionally, though Asser states that the Saxons “burst from the gates at dawn”, we could assume that this was perhaps more propagandistic than accurate, especially since Asser builds up to it stating, “For the Christians, long before they were liable to suffer want in any way, were divinely inspired and, judging it much better to gain either death or victory”.

Therefore, from the evidence, we can be fairly certain that the battle took place in the early morning, used the element of surprise as a strategy, and within the conflict, Ubba likely lost his life, though the exact nature of how is unknown.

The Aftermath

It is thought that Ubba’s defeat left Guthrum’s advance overstretched in Wessex. Perhaps Odda’s men were able to reinforce Alfred’s army, and the loss of such a renowned leader of the Great Heathen Army, as well as the fabled Raven Banner, caused uneasiness amongst the attackers.

It is often seen as the turning point in the conflict, though total victory was never fully achieved, even at the final battle of Stamford Bridge. Following Ubba’s defeat, Alfred was able to raise his army and beat the Vikings back until peace was achieved at the battle of Edington in May of 878. Following the battle, Guthrum converted to Christianity, and a treaty was drawn up, requiring Guthrum to leave Wessex and return to East Anglia, which was now a part of the Danelaw, the new central Viking kingdom that encompassed the previous kingdoms of East Anglia and Essex, as well as large parts of Mercia (now defunct and split between the Danelaw and Wessex), and Northumbria.

Additionally, the death of the Frankish Emperor, Charles the Bald, in 877, left Francia in a period of political instability; therefore, many of the Viking war bands who had fought with the Great Heathen Army, especially one particular army that had gathered at Fulham to continue the war with Alfred, instead departed to take advantage and ravage the Frankish lands.

Still, though, Wessex was far from peace. Returning from Frankia in 892, two years following Guthrum’s death, the battle-hardened and undoubtedly much richer Vikings returned with two hundred and fifty ships and were reinforced by a further eighty. They relaunched attacks on Wessex; however, these attacks were far from the organised military tactics of the decades prior. Instead, they were smaller-scale raids and attacks. With little reason for the Vikings to continue their raids on Wessex with their fortune from Francia and their new rich arable lands in the Danelaw, the Vikings disbanded in 896. Many retired to live the lives that they had originally fought for, to be farmers and to produce food in a more hospitable land than the rugged Scandinavian wilderness, whilst others joined further raids into Europe, the Mediterranean, and North Africa.

The success of the Great Heathen Army is often mentioned but overlooked. It is true that Alfred did (sort of) claim victory over the Vikings, but only for the kingdom of Wessex. By the 910s, Alfred’s son, Edward, had launched campaigns into the midlands, taking a large portion of the Danelaw, and by 954, after further campaigns by Æthelstan (the first king of the united “English” and son of Edward) and his half-Brother Edmund, Northumbria was fully under the rule of the English King. But this was not to last. In the autumn of 1015, Cnut the Great, at the time a Prince of Denmark, landed in Wessex with 200 longships and an estimated military of 10,000 (comprised of mercenaries from all over Scandinavia and perhaps some from Poland). By 1017, Cnut was crowned king of England. He ruled for nearly twenty years, being described by some as one of the most effective kings in Anglo-Saxon history (Cantor 1995). Cnut later received the titles of King of Denmark and King of Norway, creating a “North Sea Empire”. His son, Harold Harefoot, succeeded him as King of England, and Harold was succeeded by his half-brother Harthacnut. Upon the death of Harthacnut, Edward the Confessor, again, his half-brother, took the throne. Edward was the son of Emma of Normandy (Cnut’s wife and the former wife of Æthelred the Unready, who was the great-great-grandson of Alfred the Great). Edward restored the house of Wessex, but was succeeded by his brother-in-law, Harold Godwinson, in January of 1066. Harold’s family had been allied to Cnut and were rewarded as the Earls of Wessex.

William the Bastard (later Conqueror), Duke of Normandy, had claimed that he had been promised the English throne by Edward, and Harold had sworn to uphold this agreement. And by the summer of 1066, William’s forces landed, achieving a victory over Harold and installing William as King of England. The rest is history; however, due to William’s Viking roots, when the lands of Normandy were gifted to the Vikings in return for Viking protection of the lands for Francia, it would seem that overall, the Viking incursion of England has proven to be rather effective, since they eventually came to rule all of England albeit as Normans.

Nevertheless, the Battle of Cynwit was a small battle within the wider context of the Great Viking Invasion; however, its role was vital. Leaving Guthrum overstretched in Wessex, it allowed Alfred the Great to muster his army and to beat back the Vikings and defend the Kingdom of Wessex. To think that this battle (most likely as I have argued) took place on the fields between Cannington and Combwich, an area where hundreds of Hinkley Point workers drive past every day, shows the magnitude of history that has been lost and forgotten due to discrepancies in sources or assumptions that people would forever know where “Cynwit” was. We may never know for certain where this battle took place. Perhaps it occurred near Bideford or Great Torrington (another potential location for the battle); however, from the evidence presented and recorded, as well as further geographical and contextual analysis, Cannington Camp, for me at least, is the most likely candidate. But only further archaeological excavations in the vicinity and wider area would be able to prove it indefinitely, and unfortunately, at the moment, quarrying is quickly destroying the site.

Looking out at Combwich from Cannington Camp with the mouth of the River Parrett and Brent Knoll in the Background

Bibliography

Primary

Dutton, P.E. (2004) Carolingian civilization: a reader. 2nd ed. Peterborough, Ont: Broadview Press.

Keynes, S. and Lapidge, M. (1983) Alfred the Great: Asser’s Life of Alfred and other contemporary sources. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Snorri Sturluson (1990), Heimskringla, or The Lives of the Norse Kings. English translation by Erling Monsen & A. H. Smith., Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Somerville, A.A. and McDonald, R.A. (eds) (2020) The Viking age : a reader. Third edition. Toronto, Ontario; University of Toronto Press.

Swanton, M. (2005) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Liverpool University Press.

Secondary

Abels, R (1998). Alfred the Great: War. Kingship, and Culture in Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Routledge.

Albert, Edoardo; Tucker, Katie (2014). In Search of Alfred the Great. Stroud: Amberley Publishing.

Bolton, Timothy (2009). The Empire of Cnut the Great: Conquest and the Consolidation of Power in Northern Europe in the Early Eleventh Century. The Northern World. North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 A.D.: Peoples, Economies and Cultures. Vol. 40. Leiden: Brill.

Cantor, Norman (1995), The Civilisation of the Middle Ages

Heath, Ian (1985). The Vikings. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

Hindley, Geoffrey (2015). The Anglo Saxons. London: Robinson.

Hjardar, Kim; Vike, Vegard (2001). Vikings at war. Oslo: Spartacus.

Kendrick, T. D. (2004). A History of the Vikings. Courier Dover Publications.

Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael (1983). King Alfred. Penguin Books

Lavelle, Ryan (2003). Fortifications in Wessex c. 800-1066. Oxford: Osprey.

Munch, Peter Andreas (1926). Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes (English : Reiss. [of the ed.] New York: American-Scandinavian Foundation ed.). Detroit: Singing Tree Press.

Sawyer, Peter (1962). The Age of the Vikings. London: Edward Arnold.

Sawyer, Peter (1989). Kings and Vikings: Scandinavia and Europe, A.D. 700–1100. London: Routledge.

Smyth, Alfred P. (1995). King Alfred the Great. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stenton, FM (1947). Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press

Trow, M. J. (2005), Cnut – Emperor of the North, Stroud: Sutton

Leave a comment